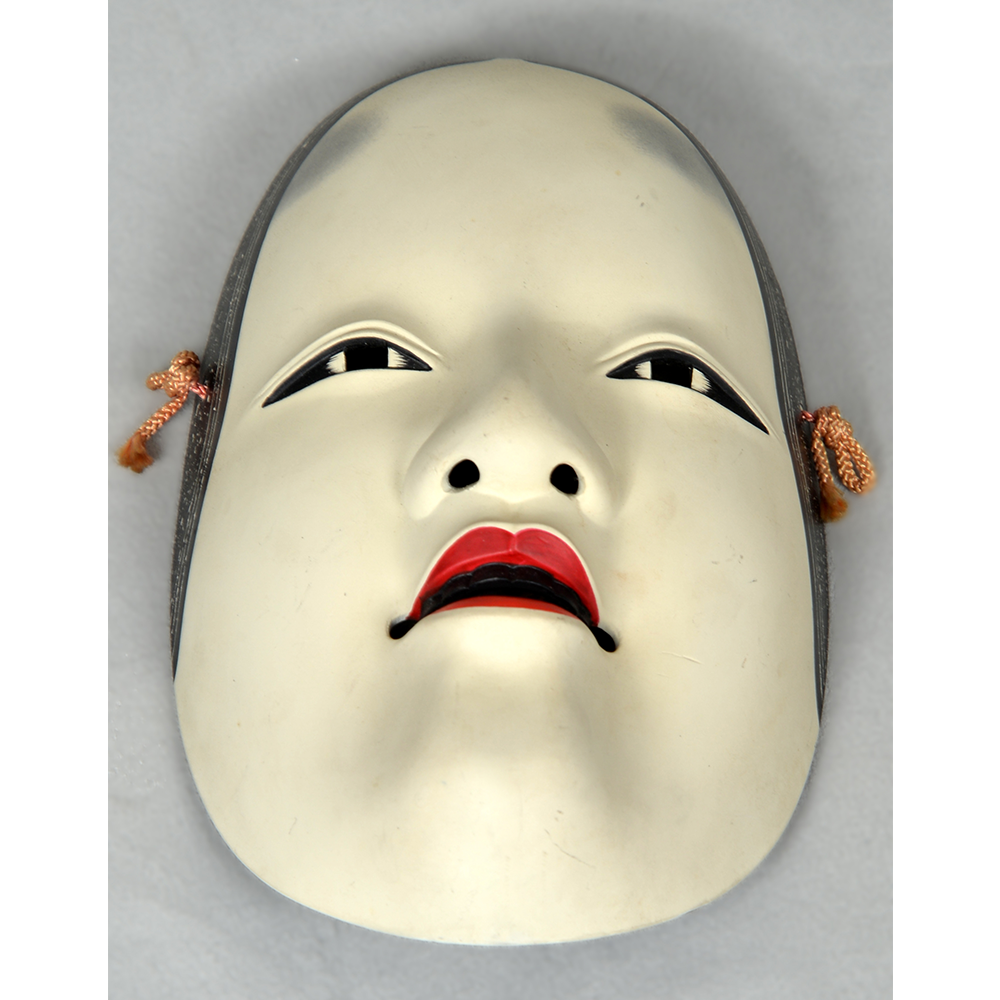

TITLE: Halloween Skeleton Mask

TYPE: face mask

GENERAL REGION: North America

COUNTRY: United States of America

ETHNICITY: Mixed

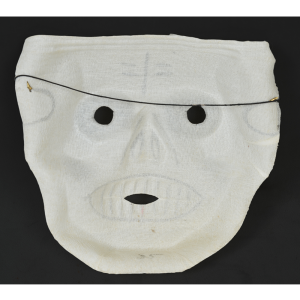

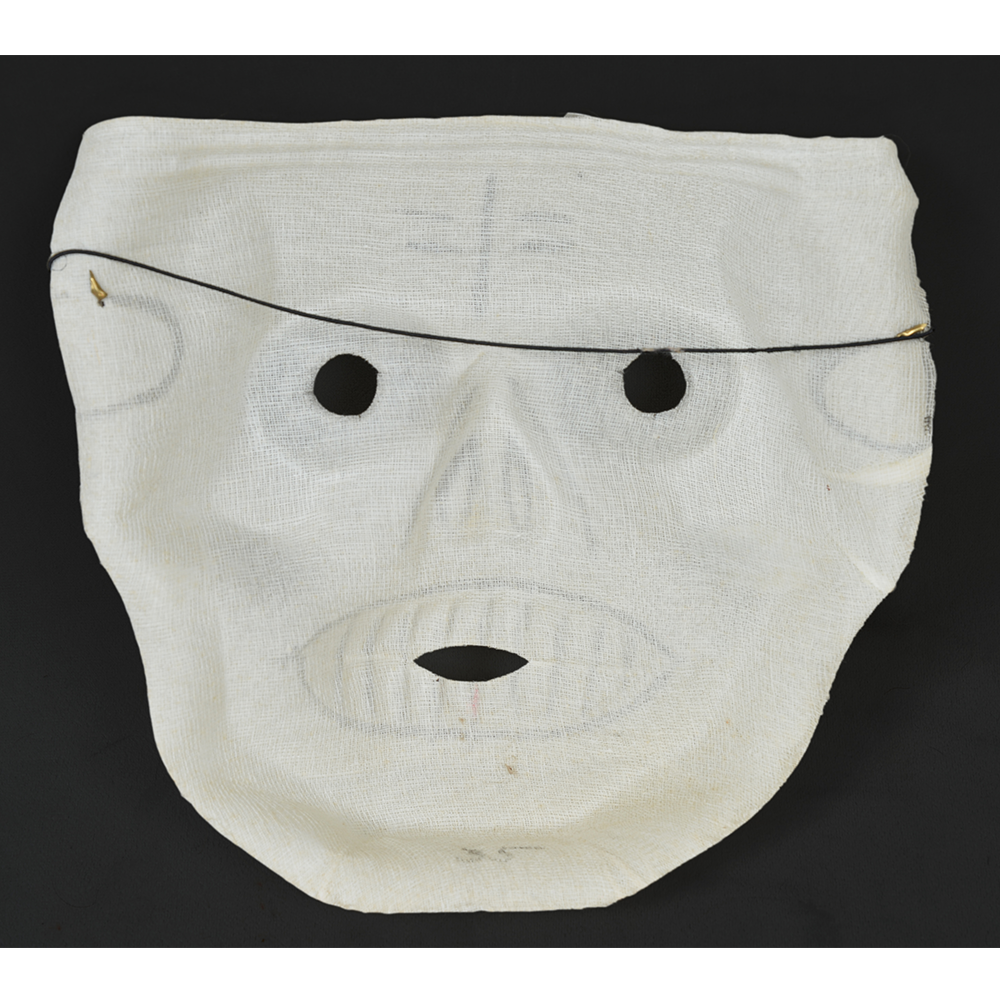

DESCRIPTION: Buckram skull mask

CATALOG ID: NAUS022

MAKER: Unknown

CEREMONY: Halloween

AGE: 1940s

MAIN MATERIAL: dyed buckram

OTHER MATERIALS: paint

Halloween is one of the major secular festivals in the United States, celebrated on October 31st each year. It originated in pre-Christian times, possibly among the ancient Celts, who practiced Samhain in late fall by wearing frightening costumes and lighting bonfires in mid-autumn to scare away ghosts. In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III declared November 1st as a day to honor all the saints collectively. The celebration prior to this All Saints Day became known as All Hallows’ Eve (hence the shortened name, All Hallowe’en, eventually elided to Halloween), and involved many of the same traditions practiced by the Celts.

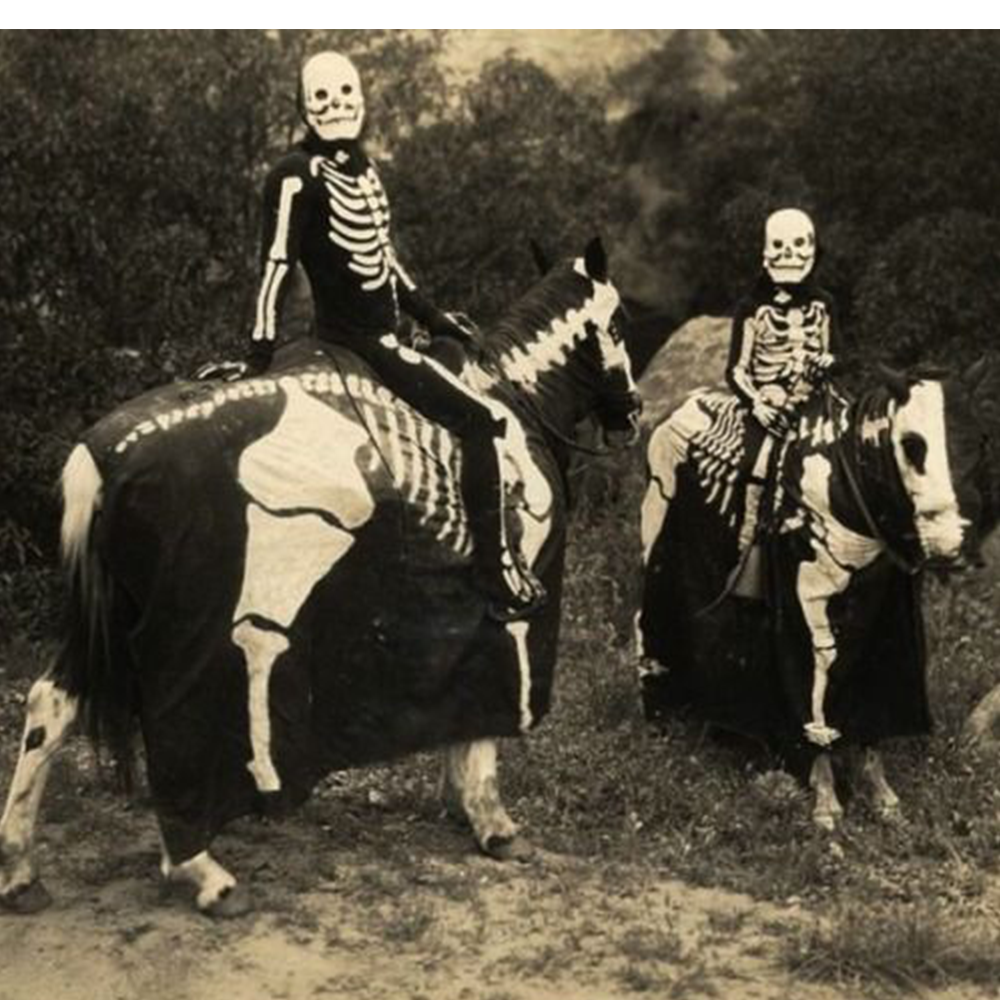

Halloween formerly had many traditions that varied by region. In modern and relatively homogenized practice, Halloween generally has three main components: costumed parties, “trick-or-treating,” and haunted houses. Costumed parties are the modern descendant of social activities designed to honor the saints and create solidarity in the community. Children’s parties typically involved games with prizes, such as bobbing for apples and carving pumpkins and other relatively dry squash into frightening “jack-o-lanterns” with candles inside for illumination. Adult parties commonly involve less innocent games and elaborate decorations to create a scary mood.

Trick-or-treating is the children’s practice of wearing scary costumes to extort candy and other sweets from neighbors. Like roaming goblins, the monsters visiting the house would demand a treat or threaten to play a nasty trick on the neighbor. The threat is of course a formality, as sharing candy with trick-or-treaters is considered a mandatory practice for friendly and community-spirited neighbors. In modern practice, many children have abandoned the tradition of wearing frightening costumes and have leaned toward fantasy characters such as superheroes, princesses, and fairies.

Haunted houses are a relatively modern innovation. They may be designed and staffed by volunteers or for profit, and generally take the form of a decrepit mansion haunted by ghosts, mad scientists, monsters, the walking dead, etc. The idea is to inspire terror and wonder in a factually safe environment.

In addition, many Americans celebrate by watching horror movies (the release of which Hollywood times to coincide with the Halloween season), and in some regions, most notably Greenwich Village, Manhattan in New York and Salem, Massachusetts, major costumed parades are organized each year. In many cities, “zombie walks” composed of masses of costumed zombies have been organized as well.

Popular masks and costumes include devils, zombies, skeletons, vampires, werewolves, mummies, witches, pirates, political figures, and characters from popular culture, such as Frankenstein’s monster. However, Halloween costumes can include almost anything, including inanimate objects and abstractions. The choice is limited only by the imagination of the masquerader. Masks and costumes depicting offensive racial stereotypes, popular prior to the 1980s, are no longer widely used.

This specific mask, representing a skull, was made from dyed buckram, moistened and dried over a form, then hand painted with details. Such mass-produced masks were popular among the middle class in the 1920s to 1950s, when they were replaced by vacuformed plastic.

For more on 20th century American Halloween costumes, see Phyllis Galembo, Dressed for Thrills: 100 Years of Halloween Costumes and Masquerade (New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc., 2002).