Guest Blogger

Dr. CedarBough Saeji, scholar of Korean dance drama

The Republic of Korea protects fourteen mask dance dramas as National Intangible Cultural Properties (gukga muhyeong munhwajae). A handful of other mask dance dramas are offered lesser governmental protection as Regional Intangible Cultural Properties (si/do jijeong muhyeong munhwajae). The system for protecting Korean heritage has allowed a remarkably large number of traditional arts to survive until the present day. The dramas from the Republic of Korea are still based in their historic hometowns, where they are leveraged by local governments for cultural pride, used for regional branding, and obligated to participate in regional festivals and events. However four of the nationally protected dramas are originally from towns in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and are now based in Seoul and Incheon.

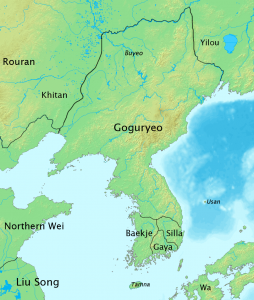

Although links to previous periods exist, the form of the dramas today was established during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). The Yi family of Jeonju established Joseon, using Buddhism as a scapegoat to legitimize the usurpation of power from the Goryeo Dynasty’s last king. Confucianism and Buddhism had both arrived in Korea around the same time and were formally adopted by the ancient kingdom of Goguryeo in 372. The two ideologies played complementary roles in Korean society. Confucianism was linked closely to governmental processes, and knowledge of the Confucian classics served as the basis for the civil service examinations. Buddhism fulfilled religious functions such as answering metaphysical questions and providing hope in times of crisis. Over the course of the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392), however, the temples grew more and more powerful, serving as tax shelters and reducing the power and authority of the crown. Yi Seonggye, the general who became the first king of Joseon, was advised by his Prime Minister Jeong Dojeon to make Buddhism the scapegoat for Goryeo’s failing strength and establish Joseon as a kingdom with a policy of suppressing Buddhism and strongly supporting Confucianism. During the Joseon Dynasty money spent on performances and rites was continually cut back, and existing performers were increasingly drawn from the general (often lowest class) population.

The history of Korean mask dance dramas has been studied by many scholars—mostly early scholars of Korean literature, whose primary goal was to salvage the disappearing dramas from oblivion. Their work began tentatively during the Japanese colonial era and gained steam in the early 1960s. The paucity of historical documents about the dramas is a function both of the attitude of the upper class towards the dramas and of the scarcity of literate individuals from beyond this elite group. The early modern period yields a few records, such as photographs by foreign travelers and early Korean folklorists. To overcome the lack of records, oral interviews with elderly performers who had learned and practiced before and during Japanese colonization (1910-1945) were extensively utilized.

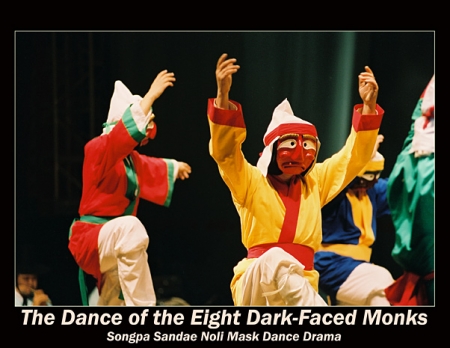

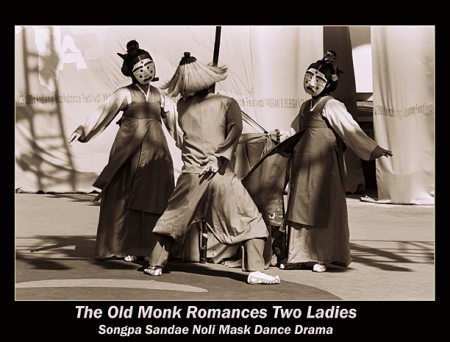

Because at the time of their development Buddhism was suppressed and powerless, and the upper class held its position at least in part due to its knowledge of Confucianism, the mask dance dramas reflected the tastes and perspectives of the lower classes in how they treat both Confucian literati (officials and those who aspire to places of power) and Buddhist monks (who had been driven from the cities, but still often religiously served the lower class). Mask dance dramas, generally performed once per year, were part of festivals that allowed for a temporary suspension of normal social rules and the releasing of acrimony directed at the elite in a way well documented in masking traditions from many corners of the world. Mask dance dramas have oft-repeating themes such as the infidelity and even stupidity of upper class men, Buddhist monks who give in to temptation, and include what literati derided as “superstitious” practices designed to banish ghosts and evil spirits. Players fart, simulate intercourse, and fight—most scenes are meant to be humorous from start to finish.

The variation in Korean mask dance dramas, however, is extreme, making it hard to generalize further. Some dramas are non-verbal, while others have extensive dialogue. Some dramas rely on extensive dance sequences, while others are based in acting. All characters were historically played by men, and consequently most “female” roles are non-verbal, as are most Buddhist monks. Characters do not have names, but are known by descriptors (grandmother, old monk, blue literati). As they are performed today the shortest is not quite an hour long, while the longest is over four hours, however most public performance opportunities are for an hour or less. Even the masks vary in construction from papier maché (the most common) to baskets to gourds to heavy paper to wood.

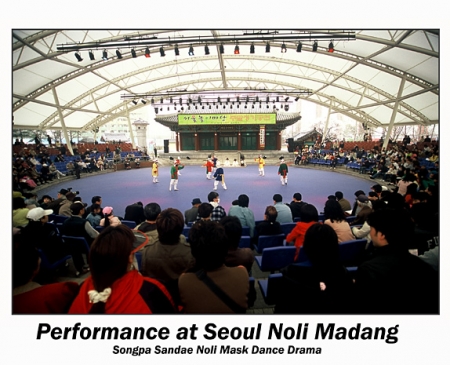

Turning mask dance dramas and other arts into heritage in the modern era meant overcoming substantial social prejudices—both performers and audiences were motivated to escape historical class divisions reinforced by performing or watching dramas. Governmental involvement, however, brings unavoidable side-effects, such as a bureaucratic desire to freeze the dramas in some artificially designated “authentic” form. Although interest in traditional arts grew strong among young Koreans in the 1980s, since then fewer new performers have emerged and since the 2000s it has been a struggle for many dramas to find more than a few paid performance opportunities per year.

At the same time, competitive workplaces are less forgiving of outside hobbies than in the past, and consequently younger performers are predominantly professionals making a precarious living from multiple artistic ventures, unlike the dedicated hobbyists in their fifties and above. Consider the most often performed drama, Hahoe Byeolsin’gut Talnori, which was once part of a local shamanic ritual in Hahoe village. The village became a popular tourist attraction and recently was listed by UNESCO as a historic site. The drama is performed there three times per week in all but the coldest winter months, making it nearly impossible for the performers to hold a standard job, but three days of work means they are hardly comfortable.

The mask dance dramas may be seen in performance series and at the annual Andong International Mask Dance Festival (two weeks with a wide range of performances in the early autumn) and the Republic of Korea Mask Dance Festival (two days of only Korean mask dance dramas, in a rotating location). In addition, each drama group organizes one big performance per year when every scene in their drama will be performed in a festive atmosphere. Because they are usually performed outdoors, you will find most performances in the fall and spring. If you have a chance to go to Korea, please look for them.